ATHENS

ATHENS  ANCIENT OLYMPICS

ANCIENT OLYMPICS  ANCIENT ATHLETE: AMATEUR OR PROFESSIONAL ANCIENT ATHLETE: AMATEUR OR PROFESSIONAL

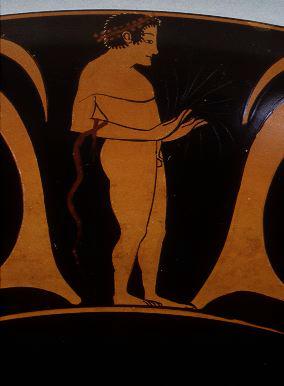

Athletic training was a basic part of every Greek boy's education, and any boy who excelled in sport might set his sights on competing in the Olympics. The Olympic competition included preliminary matches or heats to select the best athletes for the final competition.

Ancient writers tell the stories of athletes who worked at other jobs and did not spend all their time in training. For example, one of Alexander the Great's couriers, Philonides, who was from Chersonesus in Crete, once won the pentathlon, which included discus, javelin, long jump, and wrestling competitions as well as running. However, just as in the modern Olympics, an ancient athlete needed mental dedication, top conditioning, and outstanding athletic ability in order to make the cut.

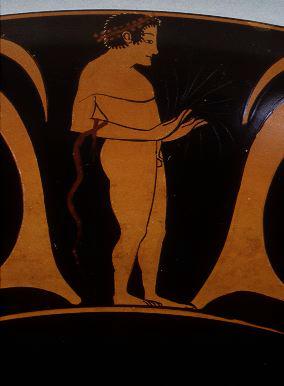

Self-confidence was also an asset. A Libyan athlete, Eubotas, was so sure of his victory in a running event that he had his victory statue made before the Games were held. When he won, he was able to dedicate his statue on the same day.

Many athletes employed professional trainers to coach them, and they adhered to training and dietary routines much like athletes today. The Greeks debated the proper training methods. Aristotle wrote that overtraining was to be avoided, claiming that when boys trained too young, it actually sapped them of their strength. He believed that three years after puberty should be spent on other studies before a young man turned to athletic exertions, because physical and intellectual development could not occur at the same time.

Victorious athletes were professionals in the sense that they lived off the glory of their achievement ever afterwards. Their hometowns might reward them with free meals for the rest of their lives, cash, tax breaks, honorary appointments, or leadership positions in the community. The victors were memorialized in statues and also in victory odes, commissioned from famous poets.

|